‘After a staggeringly beautiful drive through the fjords, I arrived in a town called Å at a collection of wooden fishermen’s huts or rorbuer, ‘ro’ (row) and ‘bu’ (live), sitting higgledy-piggledy at the water’s edge. It was love at first sight.’ – Valentine Warner

Rorbuer were originally accommodation for travelling fishermen during the Skrei (Arctic Cod) hunting season. In the earlier days, thousands of visiting fishermen and stray workers created a bustling life during the seasonal fishing, and life in the hectic winter months was often compared to carnivals in the south. With up to 30 000 fishermen attending in the 1800’s, cabin’s were limited and fishermen with many seasons behind them stood first in line.

Rorbuer were especially important at the time when fishing was conducted from open boats, without the possibility to use the boat as a residence. (Those most unfortunate had to spend their cold nights under a flipped boat on shore, willing to wake up in deep frozen clothes to get their share of the winter cod fisheries.)

Cabins in the fishing village could belong to the fishermen themselves, but were usually owned by a væreier: it was normal for the fishermen to rent a cabin from the owner with part of their catch. The term væreier is used to describe the most powerful merchants in Lofoten where the owners had all power on land – and for a period also at sea. They are also known as nessekonger – ‘peninsula king’ (Norse word for local chieftains in the Viking era.) By owning most of the land and renting out accommodation to most of the fishermen, the privileged merchants controlled all local trade and acted as a bank in many ways. It was normal for the islanders families to stay in debt for generations.

The distinct red and orange colours differentiated one fiskevær – fishing village – from another.

Everyday life

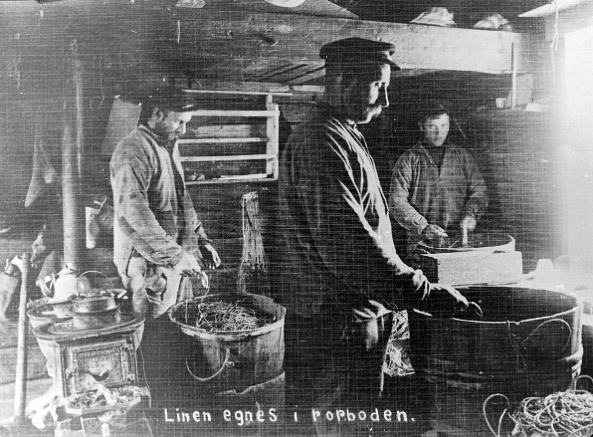

The oldest fishermen’s cabins we know of was built as simple stone and turf huts. Remnants of these still exist in Lofoten. The oldest ‘modern’ cabins we know of, had a dirt floor and wooden walls with only one room for the fishermen to eat, sleep and prepare bates. The first windows were made with kveite-sjå – the belly part of a halibut. A primitive fire pit was built between the bunk beds, with the fishermen’s outerwear and wet woollen socks hung above for drying. A dozen of so with well-used sea boots was also part of the inventory. The smell must have been – mildly put – challenging.

Built on land but with one end on poles in the water, the cabins had easy access to vessels: it was important that equipment could be lifted straight from the boat and into the house. Cabins were later built with two rooms; one where the fishermen cooked, ate and slept and the other where they maintained fishing gear and prepared bates. Depending on size, cabins usually held a minimum of one boat crew (6 people), but it wasn’t unusual with double or more. Beds were built along the walls, often two or more in height. Making enough room was challenging, and the fishermen often had to sleep two and two in one bed, often in the same clothes they used the whole day at work.

Every man brought with them a Lofotkiste – a big wooden chest with supplies such as bread, butter and dried meat, as well as extra clothing for the winter. In the hallway barrels with roe and liver were stored, waiting to be brought back on heimfarerdagen – (meaning ‘the day we go home’) when the seasonal fishery was over, and the money for their annual catch was received and distributed.

From then to now

The housing standard was improved in the 1800’s, with wooden floors, windows made with glass and a chimney to replace the primitive fire pit.

Råfiskeloven (a new fishing law) in 1936 put an end to the system of privileged merchants.

Although rorbuer are largely used as accommodation for tourists today, they are still used by sjarkfiskere (fishermen with smaller, traditional boats) that participate in the Lofoten fishing.

Fresh and dried skrei is still one of Norway’s most important export products, and thousands of fishermen still gather in Vestfjorden every winter, ready for another fishing season.

Foto: Nordlandsmuseet

Foto: Gustav Emil Mohn

We have three traditionally restored rorbu fisherman’s cabins at Holmen Lofoten.

Source:

– Lie, Jon Henrik., Serck-Hanssen, Fin. Væreiere og nessekonger. Olympia Press, 2008; Horten.

– Larvåg, Cecilie. Lofoten Vibe. Scandinavian Vibes AS, 2019.